Learning About ELF With Zig

See part 2 for this post here

ELF is an object format that is widely used in Linux and other modern operating systems. I wanted to learn about it to become more fluent in low-level code as well as start contributing to the zig self-hosted ELF linker backend.

This post will go through how I learned about the ELF format and applied it to create a minimal linker. I then used this linker on some x86_64 brainfuck code. The next post will go over how I linked and created the brainfuck code, since it relates to this “linker” a little.

Note: this “linker” does no relocations so it is not viable to link actual projects with functions and stuff. It was just a fun project to learn about ELF/x64 code.

Setting Things Up

ELF is a binary file format, meaning that humans can not read it without special tools. Here are some of the tools I used:

- hexl-mode - an emacs mode to read binary files by converting them to human-readable hex

- xxd - print binary files as hex - useful for diffing binary files in a human readable way

- readelf - this was very helpful for making sure my ELF was conforming to the ELF spec/seeing what the operating system thought of my ELF file.

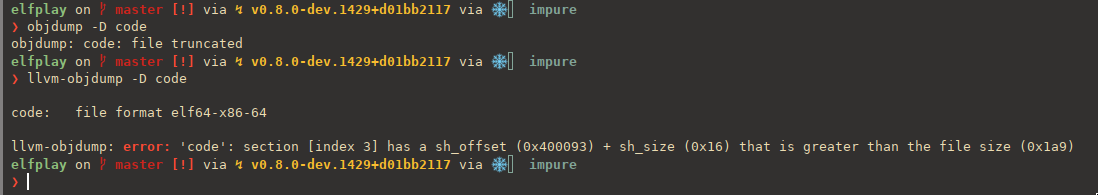

- objdump - this was useful for making sure my sections/section header table matched the spec (NOTE: llvm-objdump was much more helpful here as it was better at detecting errors/showing them

)

)

Starting to generate code

This is one of the simplest ELF files I could find online - source here - it really helped me have a good mental model of the ELF file format. Below, ehdr stands for the ELF header, and phdr stands for the program header, which tells the OS how to load the segment in to memory.

; nasm -f bin -o minimal this.asm

BITS 64

org 0x400000

ehdr: ; Elf64_Ehdr

db 0x7f, "ELF", 2, 1, 1, 0 ; e_ident

times 8 db 0

dw 2 ; e_type

dw 0x3e ; e_machine

dd 1 ; e_version

dq _start ; e_entry

dq phdr - $$ ; e_phoff

dq 0 ; e_shoff

dd 0 ; e_flags

dw ehdrsize ; e_ehsize

dw phdrsize ; e_phentsize

dw 1 ; e_phnum

dw 0 ; e_shentsize

dw 0 ; e_shnum

dw 0 ; e_shstrndx

ehdrsize equ $ - ehdr

phdr: ; Elf64_Phdr

dd 1 ; p_type

dd 5 ; p_flags

dq 0 ; p_offset

dq $$ ; p_vaddr

dq $$ ; p_paddr

dq filesize ; p_filesz

dq filesize ; p_memsz

dq 0x1000 ; p_align

phdrsize equ $ - phdr

_start:

mov rax, 231 ; sys_exit_group

mov rdi, [ecode] ; int status

syscall

ecode:

db 42

filesize equ $ - $$

Since this is just (intel) assembly, we can represent these as structs in zig:

const ElfHeader = struct {

/// e_ident

magic: [4]u8 = "\x7fELF".*,

/// 32 bit (1) or 64 (2)

class: u8 = 2,

/// endianness little (1) or big (2)

endianness: u8 = 1,

/// ELF version

version: u8 = 1,

/// osabi: we want systemv which is 0

abi: u8 = 0,

/// abiversion: 0

abi_version: u8 = 0,

/// paddding

padding: [7]u8 = [_]u8{0} ** 7,

/// object type

e_type: [2]u8 = cast(@as(u16, 2)),

/// arch

e_machine: [2]u8 = cast(@as(u16, 0x3e)),

/// version

e_version: [4]u8 = cast(@as(u32, 1)),

/// entry point

e_entry: [8]u8,

/// start of program header

/// It usually follows the file header immediately,

/// making the offset 0x34 or 0x40

/// for 32- and 64-bit ELF executables, respectively.

e_phoff: [8]u8 = cast(@as(u64, 0x40)),

/// e_shoff

/// start of section header table

e_shoff: [8]u8,

/// ???

e_flags: [4]u8 = .{0} ** 4,

/// Contains the size of this header,

/// normally 64 Bytes for 64-bit and 52 Bytes for 32-bit format.

e_ehsize: [2]u8 = cast(@as(u16, 0x40)),

/// size of program header

e_phentsize: [2]u8 = cast(@as(u16, 56)),

/// number of entries in program header table

e_phnum: [2]u8 = cast(@as(u16, 1)),

/// size of section header table entry

e_shentsize: [2]u8 = cast(@as(u16, 0x40)),

/// number of section header entries

e_shnum: [2]u8,

/// index of section header table entry that contains section names (.shstrtab)

e_shstrndx: [2]u8,

};

const PF_X = 0x1;

const PF_W = 0x2;

const PF_R = 0x4;

const ProgHeader = struct {

/// type of segment

/// 1 for loadable

p_type: [4]u8 = cast(@as(u32, 1)),

/// segment dependent

/// NO PROTECTION

p_flags: [4]u8 = cast(@as(u32, PF_R | PF_W | PF_X)),

/// offset of the segment in the file image

p_offset: [8]u8,

/// virtual addr of segment in memory. start of this segment

p_vaddr: [8]u8 = cast(@as(u64, base_point)),

/// same as vaddr except on physical systems

p_paddr: [8]u8 = cast(@as(u64, base_point)),

p_filesz: [8]u8,

p_memsz: [8]u8,

/// 0 and 1 specify no alignment.

/// Otherwise should be a positive, integral power of 2,

/// with p_vaddr equating p_offset modulus p_align.

p_align: [8]u8 = cast(@as(u64, 0x100)),

};

Note that we can provide default values for struct values in Zig. This is helpful for constants in the ELF header. Don’t mind the cast function yet, I will get to that soon. I made the default permissions for the program header read write execute for simplicity. In practice, you would use multiple program headers, some for executable code, some for mutable memory, and some for immutable memory.

Writing To Stuff

Before we write to a file, we must write the headers to a buffer so that we can add the machine code after them (we can do multiple writes to a file, but that is inefficient).

In Zig, we can represent a code buffer as a std.ArrayList(u8). Notice how Zig handles generics: a generic structure is just a function that takes a type and returns one:

pub fn Container(comptime Inner: type) type {

return struct {

inside: Inner,

};

}

const instance_u32 = Container(u32) { .inside = 1234 };

const instance_string = Container([]const u8) { .inside = "Zig Generics Are Cool" };

Since types are first class values at compile-time in Zig, lets make a function that writes our header structs to out code (std.ArrayList(u8)).

fn writeTypeToCode(c: *std.ArrayList(u8), comptime T: type, s: T) !void {

inline for (std.meta.fields(T)) |f| {

switch (f.field_type) {

u8 => try c.append(@field(s, f.name)),

else => try c.appendSlice(&@field(s, f.name)),

}

}

}

There is a lot to unpack in this function. It takes 3 things, the code buffer to write to, the type of the thing to write, and something of that type. Let’s see how we use it first.

// PROGRAM HEADERS

try writeTypeToCode(&dat, ProgHeader, .{

.p_filesz = cast(filesize),

.p_memsz = cast(filesize),

.p_offset = .{0} ** 8,

});

This is how we use it: provide our code buffer, the type of the struct and an instance of it. The function iterates over all the fields of the struct at comptime with an inline for over std.meta.fields(T), switches on the type of that field, if it is just a primitive u8, it just writes that to the code buffer by using the @field builtin. That builtin allows you to get/set a field of a struct with a comptime known string ([]const u8). Now heres where it gets interesting, lets say we have a field like this:

/// object type

e_type: [2]u8 = { 2, 0 }, // 2 in little endian form; executable

This is an array of 2 u8s. So this would use the else case in the switch as the type is [2]u8, not u8:

else => try c.appendSlice(&@field(s, f.name)), We can coerce any array in Zig ([N]T) to a slice ([]T) (slices are just a struct { ptr: [*]T, len: usize } behind the scenes) with the address-of operator & (really, a *[N]T coerces to a []T and & just gives us the pointer). We do this and then append that slice to the code buffer.

In my opinion, this is a pretty cool example of compile time meta-programming in Zig.

Note: An

inline foris aforloop that the compiler must unwrap. If it can’t unwrap it, it is a compile error. This is useful when iterating over data that you know is known at comptime.std.meta.fieldson a struct returns acomptime []const @import("builtin").TypeInfo.StructField. Here is the whole function:pub fn fields(comptime T: type) switch (@typeInfo(T)) { .Struct => []const TypeInfo.StructField, .Union => []const TypeInfo.UnionField, .ErrorSet => []const TypeInfo.Error, .Enum => []const TypeInfo.EnumField, else => @compileError("Expected struct, union, error set or enum type, found '" ++ @typeName(T) ++ "'"), } { return switch (@typeInfo(T)) { .Struct => |info| info.fields, .Union => |info| info.fields, .Enum => |info| info.fields, .ErrorSet => |errors| errors.?, // must be non global error set else => @compileError("Expected struct, union, error set or enum type, found '" ++ @typeName(T) ++ "'"), }; }

Cast Function

We have seen the cast function in use, but I have not gone over what it does. This is another example of comptime meta-programming in zig. Here is the source:

pub fn cast(i: anytype) [@sizeOf(@TypeOf(i))]u8 {

return @bitCast([@sizeOf(@TypeOf(i))]u8, i);

}

If I have a number that is a u24 (yes, Zig has arbitrary integer types up to a limit), and run cast on it, I will get the bits of that number as an array type [3]u8. What cast does is turn a numeric type into an array of u8’s. This makes it easier to deal with at the lower level, since they are all the same.

anytype means that the function accepts any type for i. This is like a parameter in a dynamic language, such as python, with no types by default. In the return type, we have a call to a builtin function, this is allowed in Zig, since, again, types are first class at compile time. We then bitcast the int into an array of its size in bytes of u8s.

This function helped me reduce a lot of repetitive code, e.g.:

e_ehsize: [2]u8 = cast(@as(u16, 0x40)),

vs

e_ehsize: [2]u8 = @bitCast([2]u8, (@as(u16, 0x40))),

This could be determined by the size of the number as we already cast it to a u16, so no reason to specify the size again in a different format.

Note: an alternative could be just this:

e_ehsize: u16 = 0x40,I didn’t want to use this because it is higher level, and to the machine, everything is a u8 and I wanted to stay pretty low level. Also comptime meta-programming is fun.

Okay, enough talking about Zig, back to ELF!

As you have seen, an ELF file can be represented as an array/buffer of u8s. To write the headers, we just look at what each field is in the header, fill it out with the appropriate value, and then write it to the code buffer. No magic! To understand the ELF file format more, I highly recommend reading the ELF article on Wikipedia and just implementing some of the structs (with hand written comments) in whatever language you use.

In an ELF header there is an e_entry field that contains the offset of the entry point (where the kernel should start executing) you can just set this to some code put in after the ELF header and program header and try executing the file!

Our buffer/file looks something like this so far:

0x00 (size 0x40):

ELF HEADER

...

e_entry: 0x00000056

0x40 (size 0x56):

PROGRAM HEADER(s)

0x78 (size however long the executable code is)

EXECUTABLE CODE

For the executable code, I just hard coded some x64 machine code into the binary like this (until I wrote a brainfuck x64 backend):

// 400078: b8 e7 00 00 00 mov eax,0xe7

// 40007d: 48 8b 3c 25 87 00 40 mov rdi,QWORD PTR ds:0x400087

// 400084: 00

// 400085: 0f 05 syscall

const machinecode = [_]u8{ 0xb8, 0xe7, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0x8b, 0x3c, 0x25, 0x87, 0x00, 0x40, 0x00, 0x0f, 0x05, 0x0 };

This loads the code for exit, loads a return code from base_point+0x87, exactly like the example in the beginning with nasm, then does the syscall.

Note: this is the exact same layout as the nasm assembly code we saw earlier.

It segfaults :(.

This is because the offset of e_entry is relative to the offset in memory not in the image/buffer/file. From what i’ve seen, linux executables are loaded into memory at 0x400000 (if someone knows why this is, please tell me!), so we must add that to the e_entry point. I have this is my main.zig file:

pub const base_point: u64 = 0x400000;

...

const entry_off = base_point + header_off;

Now we have:

0x00 (size 0x40):

ELF HEADER

...

e_entry: 0x00400078

0x40 (size 0x56):

PROGRAM HEADER(s)

0x78 (size however long the executable code is)

EXECUTABLE CODE

Now it works!

But we don’t get any output with objdump:

❯ objdump -D ./code

./code: file format ELF64-x86-64

This is because it does not have any sections (well it technically has one, the executable code), section headers, or a section header string table.

To get output with objdump, we must add all 3. Additionally, this will allow us to have different sections for bss, data, and text (code).

A section header goes after the sections (data, bss, text, shstrtab, strtab, rodata).

It is just another type of header. I define it like this:

const SHT_NOBITS: u32 = 8;

const SHT_NULL: u32 = 0;

const SHT_PROGBITS: u32 = 1;

const SHT_STRTAB: u32 = 3;

const SectionHeader = struct {

/// offset into .shstrtab that contains the name of the section

sh_name: [4]u8,

/// type of this header

sh_type: [4]u8,

/// attrs of the section

sh_flags: [8]u8,

/// virtual addr of section in memory

sh_addr: [8]u8,

/// offset in file image

sh_offset: [8]u8,

/// size of section in bytes (0 is allowed)

sh_size: [8]u8,

/// section index

sh_link: [4]u8,

/// extra info abt section

sh_info: [4]u8,

/// alignment of section (power of 2)

sh_addralign: [8]u8,

/// size of bytes of section that contains fixed-size entry otherwise 0

sh_entsize: [8]u8,

};

Now our code looks like this:

0x00 (size 0x40):

ELF HEADER

...

e_entry: 0x00000078

0x40 (size 0x56):

PROGRAM HEADER(s)

0x78 (size however long the sections are)

section .text: SHT_PROGBITS

EXECUTABLE CODE

section .data: SHT_PROGBITS

immutable data

section .shstrtab: SHT_STRTAB

the names of all the sections

section .bss: SHT_NOBITS

uninitalized data (this is special because it doesn't take any space in the executable, it only takes space after it is loaded by the kernel in memory)

section headers * how many there are (4)

Objdumped we get nice output:

❯ objdump -D ./code -Mintel

./code: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000400078 <.text>:

400078: b8 e7 00 00 00 mov eax,0xe7

40007d: 48 8b 3c 25 87 00 40 mov rdi,QWORD PTR ds:0x400087

400084: 00

400085: 0f 05 syscall

...

Disassembly of section .data:

0000000000400088 <.data>:

400088: 48 rex.W

400089: 65 6c gs ins BYTE PTR es:[rdi],dx

40008b: 6c ins BYTE PTR es:[rdi],dx

40008c: 6f outs dx,DWORD PTR ds:[rsi]

40008d: 20 57 6f and BYTE PTR [rdi+0x6f],dl

400090: 72 6c jb 0x4000fe

400092: 64 fs

The data section is just “Hello World”, but objdump tries to interpret it as x64 code so we get some weird results. And, with readelf, we get the right results too.

❯ readelf -a ./code

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: EXEC (Executable file)

Machine: Advanced Micro Devices X86-64

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x400078

Start of program headers: 64 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 175 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x0

Size of this header: 64 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 56 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 1

Size of section headers: 64 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 5

Section header string table index: 3

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NOBITS 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .text PROGBITS 0000000000400078 00000078

0000000000000010 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 2] .data PROGBITS 0000000000400088 00000088

000000000000000b 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 3] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000400093 00000093

000000000000001c 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 4] .bss NOBITS 00000000004000af 000000af

00000000deadbeef 0000000000000000 0 0 0

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info),

L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS),

C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude),

l (large), p (processor specific)

There are no section groups in this file.

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr

FileSiz MemSiz Flags Align

LOAD 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000400000 0x0000000000400000

0x00000000000001ef 0x00000000000001ef RWE 0x100

Section to Segment mapping:

Segment Sections...

00

There is no dynamic section in this file.

There are no relocations in this file.

The decoding of unwind sections for machine type Advanced Micro Devices X86-64 is not currently supported.

No version information found in this file.

To write our std.ArrayList(u8) called code to a file, it is very easy:

const file = try std.fs.cwd().createFile("code", .{

.mode = 0o777, // executable

});

defer file.close();

_ = try file.write(code.items);

Defer in zig is useful for freeing resources. A defer will execute at the end of the current block.

I wrote this post because I wanted to de-magicify how executables work. They are not some magic incarnation that only fancy compilers can output. In a few hundred lines of code, you can write a “linker” that can output an executable. With a few more, a “compiler” can be written.

All the code in this post can be found here. Note, the later commits show the brainfuck backend, so if you want to read them you can, although at the time of writing, they are not done.

We are now ready write a brainfuck code generation backend for our linker! (In the next post!)

Thanks to justanotherstrange for looking for typos and fixing them.